This rare and curious portrait, like its sitter’s smile, presents the most intriguing puzzle. Despite both artist and sitter being lost to time, this lady’s clothing captures a very precise moment in British History. Painted during the 1640s, or early 50s, it was probably produced just before or during the turbulent years of the English Civil War.

It’s dating is confirmed by the type of black bonnet which the sitter wears. This peculiar type of headwear appeared in several engravings by Wenceslaus Hollar made between the years 1641-43. Although this type of headwear has often been exclusively associated with mourning, it is likely that this item was actually a popular choice for affluent women during the colder months. Indeed, a whole folder in the National Portrait Gallery’s photographic library labelled ‘mourning’ is filled with sombre portraits of women wearing this particular accessory.

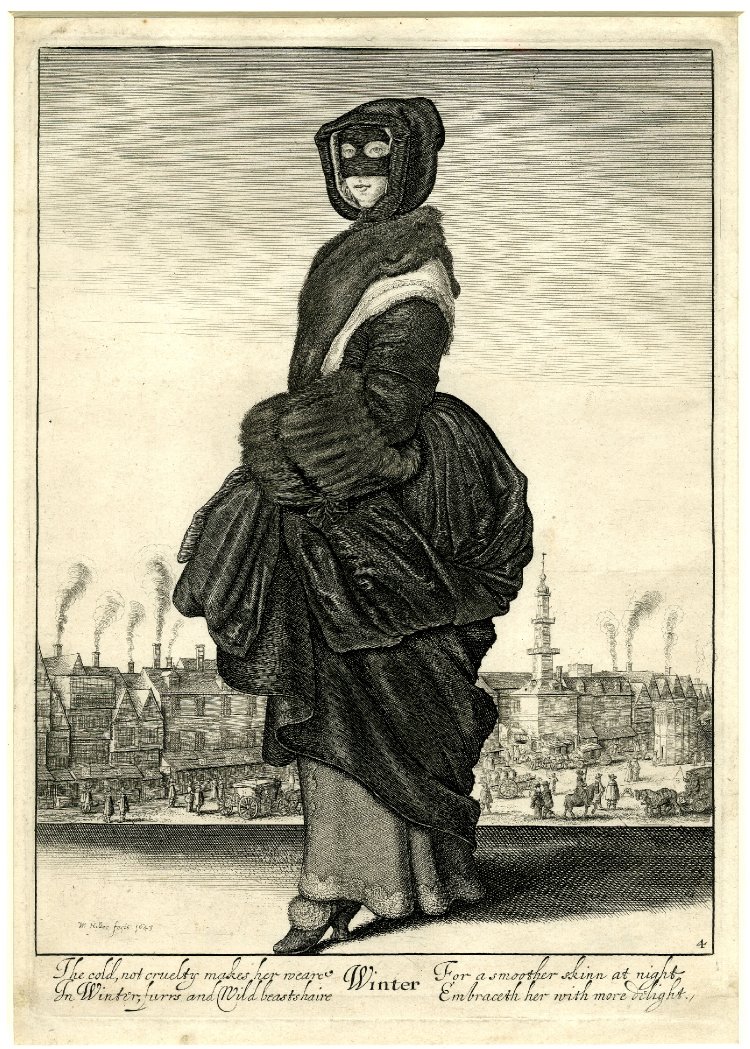

Hollar’s engravings, which often capture women’s fashion during the four seasons, associated this particularly head covering with autumn and winter. His wonderfully detailed figures are often accompanied by small verses, which often point towards its wider allegorical associations.

In an engraving dated to 1643 one reads;

Autumne

As Autumes doth mourne and wast

And if not pluckt it dropps at last

So of herselfe she feares she shall,

If not timely gatherd, fall.

The association of autumn with mourning makes a compelling case for the bonnet’s symbolic purpose. However, the verses that accompany winter, and in which the bonnet also appears, seems to make no direct suggestion to mourning at all. Yet, an earlier print, dated 1641, makes the attire’s practical purpose most clear;

Autumne

Our joy and sorrow now come both together

Autumne brings freute, but Also cold weather

Here tast the first the last you’ll feele no doubt

Except attird like mee you kepe it out.

Coupled with the brightly coloured bodice, drapery and slight smile of this young lady’s lips, these attributes help to suggest that the evocation of melancholy was not necessarily the primary purpose of the painting.

It is clear, however, that the fashion for bonnets in this fashion had died out by the Restoration of 1660. Some dress historians have associated the prominence of these head coverings with growing attempts to assert modesty in clothing during this particularly volatile political period. In 1638 a pamphlet by John Taylor was published depicting a group of women, wearing uniform pointy coifs, attacking and stripping a woman wearing her hair down. Two portraits in the English Civil War centre, purporting to be depictions of Oliver Cromwell’s mother, have further deepened the association of this headwear to the ‘puritan aesthetic’. Our sitter’s detailed lace, and colourful bodice, also make a stark comparison to our natural assumptions of the purpose of this particular fashion.

The bright and electric colouring, most evident in the drapery, looks towards painters such as Isaac Fuller and pre-empts the effortless portraits by the likes of Gerard Soest. Born out of the courtly portraiture of the likes of Van Dyck, these painters in particular often employed much more intense colouring that allowed fabrics to demand an even greater attention in the pictorial space. Set in a feigned oval, and against a moody sky, this vibrant portrait demands both our attention and intrigue.

By Adam Busiakiewicz.